Drahomíra Stuchlíková

Interview with Mrs. Drahomíra Stuchlíková

"Freedom is the biggest thing in life." ~Mrs. Drahomíra Stuchlíková

Interviewer: Klára Pinerová

This interview's English translation has been gratefully edited by Ms.Olivia Webb.

At the beginning I would like to ask you where were you born and what was your childhood like?

I was born December 19, 1919, in Karlín[1] a year after WWI. I lived there until I was six years old and then we moved to Žižkov[2]. We unfortunately stuck out Žižkov for fifty-four years. My older sister felt ashamed of Žižkov and insisted on continuing school in Karlín where she started real school.[3] I copied her and didn't want to go to school at Žižkov, so finally I went to school in Vinohrady on the Square of King George. I never finished there because I lost interest. I was about fourteen years old when my mother enrolled me in a family school[4]. I finished there in three years with two B's. Then I stepped into the real world. Later, I was employed by a private company which was Czech-German. Half the staff there was Czech and the other half was German. Bosses were both, one Czech and one German. I really have to tell you that we had a very good standard of living at that time. Then I realized maybe my life was too good and I started working in the Chamber of Commerce. I liked it a lot there and stayed there up until my arrest.

What kind of employment did your father and mother have?

After my father came back from the legion in France he was employed at the office for crushing the fraud. There was real democracy back then. No one could do just anything they wanted. No one could just think out that if an egg costs 30 hellers that he would be selling it for 50 or that someone could be adding water to alcohol or milk. My father would check all this to make sure that everything was all right. My mother was a housewife. Then I had an older sister, but she no longer lived at home because she had her own family and so we would only get together at Christmas time. Then I also have a younger sister who was placed in prison and underwent six years. In 1973 she got married in Germany and has been living there ever since.

How did March 15, 1939 look like in Prague[5]? What was the atmosphere at that time?

I really remember that well because there was sleet in the morning. When the Germans came over I was on Na Příkopě Street. They were announcing it on the radio, but I'm that kind of person who doesn't believe anything. It was horrible because in front of the Slavic House there were hoards of Germans who were enthusiastically greeting soldiers. That made me sick and so I went home.

How did you personally get along with Germans before the Munich Agreement[6]?

We got along with Germans during the First Republic. I was working in a bilingual Czech-German company and we didn't have any problems among us. I met just one person in that company who was a real piece of work. When Hitler ordered for Germans to have kids, he quickly had one more. Anyway, he wasn't r and didn't retribution denounce. Probably from 1941 onwards I was already working in the Chamber of Commerce where I worked fully for the war effort. The work in Triola, where we were making rubber masks, was organized by the Chamber of Commerce. Since they were made from rubber we would pierce them with a pin. Finally, one German came and scolded us, but we pretended not to understand. In the end they took the gas masks from us and we instead sewed underwear for German soldiers. I also have to say that we would glue glass shields onto the gas masks. We were using acetone and because acetone is harmful to your health they gave us an extra bun and milk – about a quarter liter of milk – in order to cope better with the harmful effects of the work.

Did you have problems getting food during the war?

People were getting special tickets, rationing tickets. For that we got about one egg a month; I can't really remember how much per week. We couldn't do anything about this: it was war. We didn't have any relatives in the country who could help us, and so we had to get through it by ourselves. There were a lot of people like that. The worst thing was that they took our money. I had on my credit book about 200,000 and I don't even want to say how much my parents lost. For example to get enough cloth for a dress was very difficult. Not everyone could afford this. It was very difficult, but finally we struggled through this.

What did the Prague demonstration look like?

I was in Prague then, in a basement vault at Žižkov. At Vítkov[7], there was a little chalet, and one German shot at us from there. All of a sudden, a young man walked by with a bazooka, which kind of minimized the danger. The German got him and completely tore him apart. My lady friend had his arm right behind her window; it was just disgusting. Then the Russians came and my lady friend and I wanted to go to Wenceslas Square, since we thought there would be a chance to go dancing. However, it was still off-limits, so we returned home. We didn't go out until May 9th. Prague was horribly demolished; cobblestones were torn out from the sidewalks because of the barricades that were built everywhere. Trees were in bloom as usual, just like nothing was really happening. There was a man from our building who worked at the Old Town Hall, and he got stuck in there on Saturday. He came back home after everything was over. Everyone rushed out to welcome him and he couldn't resist and fainted. He was at the Town Hall for five days and all the strain on his nerves finally caught up with him.

The time just after the War mainly revealed how greedy we were. During the rebellion they had brought a full bucket of smoked foods to the cellar. I would daily walk along the street in front of the butcher's shop and all of a sudden people came with a message that they had looted him because he was German. I didn't have a clue that a guy named Hromada could be German. They said that the food would be split up among people in the cellar. Then they took everything somewhere and I can just tell you that they didn't even let us smell the meat. I really lost my faith in people.

How did you live through February 1948?

Of course I was brought up in an anti-communist family. When someone mentioned the word communism or communist, my parents were like red cloth to a bull. We lived in Žižkov and there were tons of communists. In our house there were also some people who had a daughter and a son, plus or minus, who were in my age. We didn't want to meet them. In short, when the year 1948 came, I didn't want it.

Why were you arrested?

In the year 1948 there were elections and someone threw into our mailbox leaflets, on which was written, "Vote with white ballots." At that time I didn't have anything better to do than to bring it to work. The stance written was that people shouldn't vote, but just throw in just white ballots. I liked the idea at that time and I gave it to others to read. I never thought that it could have such consequences. Firstly, I didn't think someone could be arrested for leaflets. At the court I also told them that during the First Czechoslovakian Republic there was the slogan "vote for one, don't vote for five" and nobody was arrested. So I didn't think this could be a crime. Of course we were gripped by those leaflets and started to copy them. Someone denounced it of course, until the President of the Chamber of Commerce found out about it and called the secret police on us. It was incredibly quick.

What did your arrest look like?

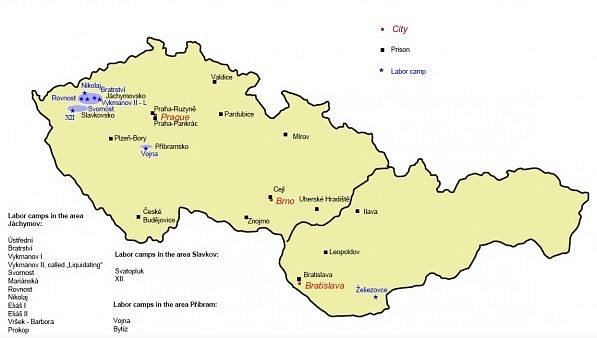

Mr. Jech called the secret police on us. They came and took us to Bartolomějská 4. I was arrested May 29th-30th in 1948. Nobody can imagine what would happen at number four at that time. We were crammed into horrible dark prison cells. In the corner there was a little wooden closet, which I thought was a telephone booth. It was a metal or iron toilet. For a walk we went out onto a little square, three by three meters. From number four they transferred me to Pankrác, where I stayed for 21 months. I was there with various people. I remember the arrival to Pankrác very well. Before check-in, they made me stand by a wall. To either side there were Gypsy women. They were all dirty and later I found out it was from blood. Then they took me to my cell. That was also surreal because from the prison square there was a big iron gate and the way that I was rushing in, well, I didn't think that it would be connected underneath. I stumbled and flew into the square, I almost spread like a frog on the floor. That was a beautiful entrée...

How did it look like at Pankrác[8]?

I quite liked it at Pankrác, I didn't miss any work. Girls were advising me to sign in for a job, so at first they put me to a place where they made bags. From there I was kicked out because I didn't get along with čůzák[9]. After that I was in laundry, printing works, and finally I ended up in a dispatch cell. That was an "eincell,"[10] but there were seven of us in there. We were supposed to make hemp rope. We blocked a toilet with the rope twice. Once we made a ball, which I took out afterwards and threw it behind the old, non-functioning printing works. On the next day, we had a walk. When we got out to the square I thought I would go nuts. One of the dogs that was running around was playing with the ball. Anyways, I finally threw a second ball there as well because I had nothing to do with it. Then we were supposed to glue flags together in the cell. That was also charming because they gave us a box of flags and skewers and told us to glue. As they didn't give us any glue, we concluded we couldn't do anything. So we put everything under a bed. Then a čůzák came and said, "Take out what you have done." We answered we didn't have anything as we didn't get any glue. So they gave us a stone vessel, full of glue. Again, we pushed that under the bed because they didn't give us a single brush. When he came up again we said we unfortunately didn't have anything since we didn't have a brush. So he took everything from us and we figured he wouldn't make us do it – that he would lose his nerves on it. We never glued anything after that.

How did the investigators behave towards you? Did any of you go through some physical violence?

Well, first of all, nobody would try that on me, and second, they were not that cruel at that time – yet. Yes, we heard shouts from next door a couple times, and how they were beating someone, but from my point of view, that would happen sporadically. All that increased rapidly in 1949. Although they were on a first-name basis with us, threatening us, calling us names, they never physically attacked me.

You mentioned your younger sister was also arrested. For what reason?

She was held as a precaution before the funeral of President Beneš. At that time I was cleaning at Pankrác and mother came to tell me. Somehow, inconspicuously, she told me in the corridor. After the funeral they let my sister go back home. Well they were really worried that people would be rioting and so they held various people as hostages. Then she was tried with me and convicted for six years.

Did you ever meet again in prison?

We met just once. She had a lesser punishment than me, and so she could get on something called “commando.” She went to Varnsdorf to an Elite factory, where nylons were made. I was sentenced to be in a normal prison, but once when I went to Chrastava, they allowed me to see her on a visit. I came over there in the afternoon, maybe more the evening, and early in the morning I had to leave again. Anyways, I was happy I could sit down with her for that moment and we chatted a little. Then she visited me when she was released. I can even tell you that two of my friends visited me. Each of them just once, but I was glad anyways, since they didn't throw me overboard. One friend kept sending me letters and also a picture of her son. I was lucky in this way since this meant that some people were unafraid to come and see me. It was real heroism to be unworried about being seen with a convicted person.

When did you have a court date?

I had a court date on June 6th, 1949. I received a notice only two days before the process. When I wanted to give it to my mother, my own lawyer jumped up and tore it out of my hands, saying I wasn't supposed to have it. She was appointed to me by the court, but she still demanded money from my parents. Mrs. Doctor Turečková had a husband who was a chairman in the Chamber of Law and so she had the high privilege to take money. My parents paid her something, but afterwards they opposed. She didn't defend me at all. She came up to the court, had blond hair, a light blue dress, and came there as a star. She didn't get me ready for the situation or how to behave at court. The only thing she said was a commentary on my hairstyle and that I shouldn't have it because it could make jurors angry. Then she asked what dress I would be wearing at court. That was all she told me for the run of the whole process. When they asked me after whether I felt guilty or not, I didn't know what to answer. Finally, I said I felt partly guilty. At that time I counted on getting twenty years. When I finally got thirteen, I was quite happy. I spent in prison twelve of them. But I did not wonder why I was given that sentence. If I was in their shoes, I would not have given freedom to a woman like me either. Today I must laugh about it, because at that time I really fought against them, and one of my lady friends kept telling me, "Please, don't look at them like that or they will never let us go home!"

Did you think you will really have to serve all the time or that you might be released early?

At that time, nobody really believed that we would have to serve the whole sentence. Even once in Litoměřice a judge came and called us over, one after another. He asked each of us when we thought we would go home. We all regretfully said we didn't know. None of us knew if we would have to serve the whole sentence. Any one of us could have died the next day.

Were you ever in solitary confinement?

I was once in solitary confinement at a judicial prison because I had sent home a scornful letter about a prison. I got a month of correction for the letter, and out of that once or twice a week in a dark room. I was starved and had to sleep on a floor. When I had a normal day, I got water for washing and a broom to sweep. In the evening they gave me a straw mattress and one blanket. Once I was also given a bucket with water to wash the floor. I didn't really want to do it, but finally I managed it. In the afternoon the guards were changing and another čůzák came and started yelling that I hadn‘t washed the floor properly. That was understandable because I didn't really give it much effort. I thought about it and then when I was given another bucket and water, I made the whole floor completely wet. He came at four o'clock and the floor was still wet, so no smudges were visible on it. He just caught his breath and left. It was terrible to sleep on a wet floor, but I risked it anyways. It made me so happy to know I took the wind out of his sails.

What was interesting was that all the čůzáks were driven crazy by my singing. I remember that when we were in Želiezovice, where we worked so hard, we were supposed to put down a ton of some rootbeet. After a couple of years, my friend wrote in a letter to me how she still remembered me, and how I had started singing. She said that if that didn't happen, she would never have been able to bear it.

What came next after the court?

After the court I went to Litoměřice, where I stayed for nine months. In Litoměřice we ended up enjoying it because since went in there with so much fear and worry. Vlasta Charvátová[11] traveled with us, with another group of people, she shot and wounded one of the guards in Litoměřice. They wanted to release some of the political prisoners there. Vlasta stayed at the gatehouse and all of a sudden this person came there and she shot him. She was lucky she got his shoulder. Vlasta finally went to apologize to him. He was a nice person and forgave her. They gave us various jobs to do, but all in all, they weren't successful. For example they wanted us to strip feathers. The girls would start to work immediately, but I told them, "Girls, have you gone crazy? Never in my life have I learned how to strip feathers." So they all stopped and if they stripped, they were making puffs for slippers, stuffing for their pillows and so on. When čůza came in the afternoon, I took one piece of feather into my hand and said, "And now please tell me, what shall I do with this feather?" She took it and from one side ripped it as well from the other and gave me the feather in one hand and the quill in the other. The girls couldn't stop laughing. After nine months, I went to Znojmo. That was also surreal because they transported us in an "anton"[12] whose door didn't work and kept opening. We knocked on the driver's and čůzák's doors twice. Twice the driver came to close it and on the third time he said we would have to hold it. So we held our door until we were in Znojmo.

You didn't think you would run away?

No, because when you have parents at home, you are thinking that this wouldn't help them at all. I had to leave these thoughts aside; it wasn't possible. Imagine this: in Znojmo we had another big laugh. There was a head guard, some Márinka, and she read out loud our names from the list. One girl's name was Ordová-Cvetkovičová. Mirka always put her hand up twice for this name. But then, when the head wanted to change us into other clothes, she counted us and it didn't match. There were ten of us and she had 11 names on her list. For god's sake, she couldn't figure it out. We kept saying, "Mirka, tell her you have got two names," but she had such a sense of humor she kept putting her hand up for both names. Finally, we made her say it. That time we had fun. In jail, there were moments when one had fun and sometimes it was just the opposite and life was difficult. So in Litoměřice and Znojmo I was in normal prison cells. I didn't get to work anywhere and was just in the prison. Then I went to Česká Lípa. In Česká Lípa it was good because the head guard of the prison was quite humane. From there I went to Liberec, where I stayed for a couple days, and from this prison they divided us into different commandos and I got to Chrastava, like I already mentioned to you. We had really awful food there because one mistress wanted to save money and kept telling us that we would get everything back for Christmas. So she would give us boiled pork all the time. I won't eat boiled pork, even if I was standing underneath the gallows. I would rather tell an executioner, "Please, hang me up already and the boiled pork will be eaten by a dog." I tried it warm, cold, salted, with mustard, but when I see boiled pork, I have nausea. Then it turned out that she stole everything she could and we didn't have anything at Christmas. In jail they were stealing among themselves. I had a violet lipstick, and when I was in Litoměřice, one čůza had the same one. Of course they didn't give me my purse back, so I found out that she must have simply taken it. From this commando, I went to Pardubice. At that time the prison in Pardubice was starting and was supposed to be a brig for the highest corrections. At the beginning there were only political prisoners. There were sewing places and a laundry, and we also went to work in the garden. So that was fine, although hazing was also quite bad there. I stayed there about two years. Then I went to Želiezovce.

Dagmar Šimková also writes about Želiezovice. Could you also tell me a bit about it?

When Dagmar Kočová once told me about that place since she had been there, but I couldn't imagine it. The truth is that there were large pieces of land. For example, you might see a little village on the horizon and think that it was a couple of steps away, but it would take half a day to get there. That was just terrible, especially for me, who never tried to go fast anyway. Girls would always go in the front and I would still be trudging somewhere in the middle. Finally it all ended when I strained my spine. From that time onwards I would suffer backpain for about 20 years. I brought a nice little gift from Želiezovce. All of us, and there were 300 of us, got jaundice. At the end I got out of it pretty well, but there are girls who are having troubles from that up till today. With jaundice it was of course me again who came down with it first. During that time we went to collect corn from the fields. I felt a pain on my right hip, by my gall bladder, and I had a higher body temperature. That was why I decided I wouldn't go to work. A doctor had also had just about enough of me and told me to bring urine, to be evaluated. A little later she flew in, told me to pack my things and so I went to quarantine since I had it on three crosses[13]. Soon after that there were others coming in. The jaundice epidemic started in 1956, when there was a riot in Hungary. Čůzáks were off-coloured since we were practically on the border. There you saw mountains that were already Hungarian. The authorities knew the rioting could easily cross over from Hungary to us, and so they had their hearts in their mouths. Right at that time we got jaundice. We all occupied a whole block of wooden houses.

Where did you go after Želiezovce?

Then I traveled to Ruzyně, for about a month, to do translations. That was a bit of variety and change. There we had only two or three guards, and others could get there. Those of us from Prague were enthusiastic because we finally had visitors and could get parcels. There was a more relaxed regime. We weren't locked in cells, could move freely and, for example, have a small chat after work. There were about twenty of us working there. Men would translate some secret stuff. We got just concepts which we would rewrite on copy stencils. Everything was highly confidential. Soon it was over though and we had to get back to Želíze.

Where did they take you from Ruzyně?

From there they took us back to Želíze and later they sent me to Bratislava. There we knitted sweaters. Never in my life was I good for knitting and I wasn't able to imagine I would someday knit a whole sweater. In the end I managed somehow, and from Bratislava, they took me back to Pardubice, where they released me. I traveled the whole country like this. To all that you must also count up the overnight breaks where we stayed in Ilava, because it wasn't possible to manage a whole trip in one haul. I was in many prisons then.

Was there any difference in the behavior of male and female guards?

Well, not really; they were cast in the same mould. Men I didn't recognize as real men. It was a čůzák to me, and that was it. In Pardubice I was in correction once and in the corridor there was a water supply where we could wash ourselves. A Čůza let me there once while talking to a man at the same time. He wanted to get in and have a look at me. I told to myself, "That isn't a man. It's just a čůzák." So I took my clothes off and washed myself. He can please himself – that wasn‘t the issue. For us the issue was the Sultan, the governor of the jail in Pardubice, that was fundamental. On the other hand, girls were often making fun of čůzáks.

And in what way?

Well for example once, they decided they would re-educate us. So they started giving us some lectures. The girls would always put their hands up and ask about something. For example, something about Masaryk. Then the čůzák said, "Well, I don't know that – I must ask about it, I will tell you next time." The next time he didn't show up there of course. You know, there were many stories running around about the way they spoke. For instance, instead of “tin foil” they would say, “tin loif.” Once, when I was in Chrastava on commando, one of them hinted for us to sign a socialistic commitment[14] with the promise that they would send us home earlier. When he was done with his speech, Bohuška and I put our hands up and said, "Mr. Commander, we can't sign it. We are not provided with all the human rights from court. Our signature has no weight." And so we broke it down.

Were the criminal prisoners more susceptible to re-education or to signing various work commitments?

Some of them were, of course. I think that some woman who had kids at home were more liable to this. One of my lady friends, who I have been friends with up till nowadays – and I still reproach and blame her for it – signed the cooperation agreement. She simply wanted to get home because both of her parents were sick and her son, who was in the army, had gotten a very serious infection of jaundice. She knew she couldn't help them out while in jail. Up till today she has had troubles with that though, because nobody ever asks her “Why? Why did she sign?”

How did you get through visits of your friends and relatives and how long did they last?

The visits were a chapter in itself because it always depended on the čůzák who was present at the visit. It happened to me once that my father came to Litoměřice; and we welcomed each other; and I asked about mother; and the čůzák ordered the visit to end right there. When the čůzák was full of spite, he didn't give you the pleasure to have a visitor. Once in Pardubice, I couldn't get nuts and candies that were in a parcel, it was simply forbidden at that time. And so they took it out and stole it. It always depended on their moods; how well they slept. We were dependent on all of that. We were always looking forward to having a visit, but when they left, we were so sad...you knew you had another long time ahead before you would see them again. Sometimes I said to myself that people who visited had it worse. In front of the gates the visitor had to beg and plead because the guards would also harass them. Visitors worried about whether the parcel would be delivered and how long the visit would take and so on.

How often did you have visits?

According to the prison order, it was allowed once a month – but if you did something bad, they could stop or shorten it. When I was on the command, visits were more relaxed, and sometimes a parcel could be handed over. At Pankrác the parcel was properly checked. Well, when you think about it deeply, when they were giving you a parcel at the beginning of prison, they had to take it away from their own mouths since there was still a ticket system[15] So we didn't really care for the parcels much.

In which prison did you experience the worst hunger?

I was starving the most in Bartolomějská prison, because there they had tin pots and when they gave you black slops in the morning, it smelled like the previous day's goulash, and when you were seved something different at noon, it smelled like the black slops again, which they called “noble coffee.” At Pankrác I once again got back to normal. On weekends, we would get an egg for lunch and bread for supper but they didn't fuss about us. Anyways, when we would go to work – for example to the printing works – we would then get one bratwurst and a bun. But nowhere else did we get anything better.

What did the institution clothes look like?

It was like what a household provided. In Litoměřice it took 14 days before we were changed into the institution’s clothes. At the end we were given rags from German soldiers. There we struck a blow when we tore them apart, wherever it was possible, and we set out on May 1st for walk. Then they gave us some better clothes. Winter stuff was from furry, hairy cloth and summer clothes were with stripes. I was glad we were getting clothes because my parents couldn't provide them all the time.

Was it possible to borrow books?

Yes, it was. At Pankrác it was written, "Whoever damages it, pays for it, and will be strictly punished." We had quite old books there, but in Pardubice it was better. On the other hand, when a better book arrived, it was wanted by everyone, so we had to wait until someone finished it. You could borrow about three books per month.

Were there ever any conflicts arising among you?

Well, there were some of course. There were some distractions in Pardubice; for example you could go out to the square, but you could never avoid being in a cell with someone you didn't get along with. For instance, there was a Slovakian girl who was really nasty to me. I understood her, though, because the prison was getting onto her head and nerves. But it still didn't give her the right to spoil the life of others around her. The worst were the sisters who always quarreled. Also, I wasn't always nice, but I tried hard. Conflicts would begin from trifles. Conflicts would never come out of politics because those would fall apart. There were girls from all politic parties and various religious sides. It could always happen that you said something and insulted somebody. I would rather call it a submarine syndrome.

Do you remember a hunger strike in Pardubice in 1955[16]?

I also took part in that at that time, but I wasn't a mover. They still put me in a hole, though. There I wanted to continue on a hunger strike, but they told me they had agreed to something and everything was over. I think it began due to sanitary towels because some of the girls reacted badly to them. I don't know whether they wanted to increase the allowance or be able to buy them with their own money. I really don't remember that.

What was hygiene like in prisons? How often could you wash yourself for example?

It was quite alright in Pardubice. On each floor there was a big bathroom with a big tin trunk. There ten girls could wash at once. In Želiezovice there were French toilets[17] and there were mice and rats. In Želiezovice it was like the Middle Ages. Terezka Procházková was always saying, "When I see a mouse on the square I tell myself, ‘Yay, a little sparrow. And when I see a rat, ‘See, a pigeon.’" This way she was consoling herself to not be afraid. You know, when you go to a toilet and there is a rat watching you, it is nothing funny.

Some girls tried to keep up hygiene. They would come from the fields, load everything into a manger, wash it, hang it up and in the morning they went to work in clean clothes again. We tried to wash and shower. In Pardubice, it was more civilized. There we went to showers with warm water once a week.

How were you released?

I was released on amnesty. Initially we were supposed to go home on May 9th, but because one čůza needed help with ironing, I was released on May 10th. I got 375 Crowns ($20 dollars today) as earnings for 12 years. I had a blouse and a borrowed skirt. Everything else I had was stolen. They stole my book of English and clothes. In Pardubice they bought us train tickets and we went home.

Did you have troubles finding a job?

I must tell you, I was really lucky, because our girls always helped me. After discharge I went to the work office to hand in my papers and then I flew around the town. I met one lady friend who asked me what I was doing. At that time I really didn't know what I should do. She told me she was just on her way to the Žižkov storage area since they were hiring. We went there together and both were hired. I would pull pallets there, in which there was loads of chocolate, even though I was pregnant. After delivery I didn't go back to it. After another three years I was looking for a job, but I was so simple-minded that I always told everybody I had been in prison. Of course they never gave jobs to convicts back then. Then another lady friend spoke to me on a tram, asking, "What are you up to?" I told her I did nothing. "And would you like to go to my work? I´m giving it up." She was a storekeeper in a big factory, but only formally on a paper. There I got a questionnaire and there they asked me what I did in the past. That time I wrote that I was sewed clothes for a firm in Hradec Kralove that never existed. That was good, but if I wrote down I was in a criminal, it would never work. Eventually everybody would know anyways, but that didn´t matter anymore. I stayed up until the time when they built a new factory in Stodůlky. I didn´t want to commute from Karlín to Stodůlky, so I wandered around in the streets again. I met a lady friend and she asked, "What are you up to?" "Nothing, looking for a job." She told me to go to her husband to be a housekeeper and I did that until I went to retire. My girls always helped me.

How did your old friends behave to you after you came back?

My two best friends, who also visited me once in prison, stayed with me forever. I never tried to get in touch with the others again. I didn't have much to talk about with them and had no inclination to meet them. It was like I was in another world. I was only able to speak to people who were arrested like me. It didn't matter whether it was a man or woman. Finally, I also married a mukl[18] who was in prison for 11 years. He had so many friends and so did I. At Easter and Christmas I kept writing and sending so many postcards, it seemed impossible. While we were at our cottage, we never had one free Saturday or Sunday alone since someone would always come for a visit.

How did you perceive the year 1968?

I was with my son at the cottage when my mother-in-law came and told us that the Russians came. A week before that, our relatives from Vienna had come over, telling us the Russians would occupy our country. I got really furious then and said, "If they will occupy us, that means they will occupy you as well. Just remember how it was during Hitler's era." He got really mad at me. Curtly, he said that in Vienna, they had known that much earlier than we did. We have a cottage on the Sázava river, where the tanks went through and made a huge noise. We just watched what was happening. I would have never allowed it. I always thought it was impossible. Then I saw the after-effects, how they were shooting at people on Vinohradská Street. Don't ever tell me they were brothers.

Did you, after the August 21st arrival of the Warsaw Brigades[19], have any problems at work?

No, I formed my principle for this: that I will never deny it. Also, that I will never start talking about it. However, I had to break this rule once. At one time, I was at a cottage with my son and the neighbors from next door had a little girl, who was going to kindergarten. She asked, "Mrs. Stuchlíková, were you in prison?" That was the first time when I denied it because I told to myself that kid doesn´t need to know anything about it. I was mad at her parents, though, because they should be more careful when talking in front of kids. I also didn´t want to admit it because of my son – so he wouldn't have problems out of it. He knew about his dad because he knew his dad’s friends. Finally, we had it all out in 1989.

How do you recall the year 1989 in your memories?

I wasn´t in Prague at that time, so I didn´t know much about it. I didn´t go back to Prague before the Confederation started to be formed. I couldn´t care about it that much because my husband was very ill.

Do you have any health problems from the experience in the prisons?

In Želiezovce I strained my back after the first month and I suffered from that for another 20 years. Other girls had problems mostly from the jaundice, which I have told you about already.

When were you rehabilitated?

I was trying to do that already in 1968. I had a Judge Bohdana Smolíková, or something like that. In her speech, she made a murderess out of me, because I had one accomplice, who was sentenced for one year. I hardly knew him, but during the twelve years I was in prison, he died. She blamed me for his death. So the rehabilitation ended with another fiasco. Then I was rehabilitated in 1989 without any problems.

Would you be able to forgive them for all the injustice?

You know, the thing I minded the most was living behind the bars. When someone complains how badly we were treated there, I would forgive them all that. Even if the bars were made from gold, they could never be a substitute for freedom. Freedom is the biggest thing in life.

What helped you to live through the years you were in prison?

I think it was anger. I'm not a person who would cry out – but when injustice happens to me, I then get very angry. Finally, there is life as well in prison: you have some fun, but there are also terrible things happening there. We had to live through everything. Don't forget to put this in. There are about twenty of us who were in prison, and whose husbands were in prison, and we don't have the pension money and we will never get it.

Thank you very much for the interview.

[1] Karlín – Prague district.

[2] Žižkov – Prague district.

[3] Family School – a school designed for students who wanted to gain knowledge and skills useful in everyday and family life, wanted to expand and deepen general education.

[5] 15th of March 1939 – the date in which Germany start to occupy Czechoslovakia.

[6] Munich Agreement – an international treaty signed in Munich on 29th of September 1938, wherein representatives of four countries – Neville Chamberlain (Great Britain), Édouard Daladier (France), Adolf Hitler (Germany) and Benito Mussolini (Italy) – agreed that Czechoslovakia must give up the Sudetenland to Germany, Poland and Hungary. Representatives of Czechoslovakia were present, but not invited to the deal itself. Up until today this agreement has been a painful and controversial topic in Czech history.

[7] Vítkov – an extended hill on the right bank of the Vltava river which forms a border between the Prague districts of Karlín and Žižkov.

[8] Pankrác – one of the biggest and well known prisons in Prague.

[9] A guard (read [chou:sack]; a slang word from prison for a gaurd, in Czech language it comes from the word „bitch").

[10] “Eincell” – a cell for one person.

[11] Vlasta Charvátová – a dissident who was born on the October 19, 1925, and studied at the Faculty of Arts and Philosophy at Charles University in Prague. After her studies she made a living as an interpreter. She was arrested when she wanted to help her friends break free out of a prison in Litoměřice on August 22, 1949. She was shot and wounded during the attempted rescue; a guard and the whole group was arrested. Vlasta herself went through brutal interrogations and she aborted during that time. Her husband was sentenced to the death penalty, but Vlasta Charvátová was sentenced for life. She was released 18th of December 1963.

[12] “Anton” – a closed police van for the transport of prisoners.

[13] Three crosses – a pattern of symbols used to mark dead bodies. Here it suggests that Mrs. Stuchlíková was seriously ill.

[14] Socialist Commitments – contracts where prisoners obliged themselves for to work extra hours or also on Sundays and national holidays to receive various privileges, e.i. to write more letters home, to get more parcels. They were also promised an earlier release.

[15] Ticket System – form of the food service of consumer products, in which state authorities determine the types and quantities of products which are issued regularly or one-off vouchers for various categories of consumers. With rationing ticket system state tries to satisfy basic needs of the population at the time of general scarcity of goods (especially during the wars and postwar periods). Side effects of rationing ticket system is illegal black market. Rationing ticket system is often combined with free legal selling at higher prices than the rationed goods. In the Czech lands there was rationing ticket system during World War I, immediately after its ending and in the years 1939-1953 (removed monetary reform).

[16] Pardubice Hunger Strike – Approximately 520 women prisoners denied themselves food in September 1955. Some withstood pressure for a week, others even longer. Primary reasons included bullying from guards, bad food, inadequate sanitary napkins and bad working conditions. The initiators were sentenced to solitary cells and others could not send and receive letters or have visits.

[17] French toilet – special toilet system when the toilet does not have a porcelain bowl but instead only a hole in the floor and two steps for feet.

[18] “Mukl” – an individual who was in prison. The word "mukl" itself comes from the abbreviation of "a man on death row".

[19] Warsaw Armoured Motor Brigades – The Polish Army’s motorized unit which arrived following the Warsaw Pact. The Warsaw Pact, also called “The Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance,” was an army mutual-defense agreement of the European countries of the Eastern bloc which existed from 1955-1991. Representatives of Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Germany, Poland, Romania and U.S.S.R. in Warsaw signed it into effect on 14th of May 1955.